About lenticular printing

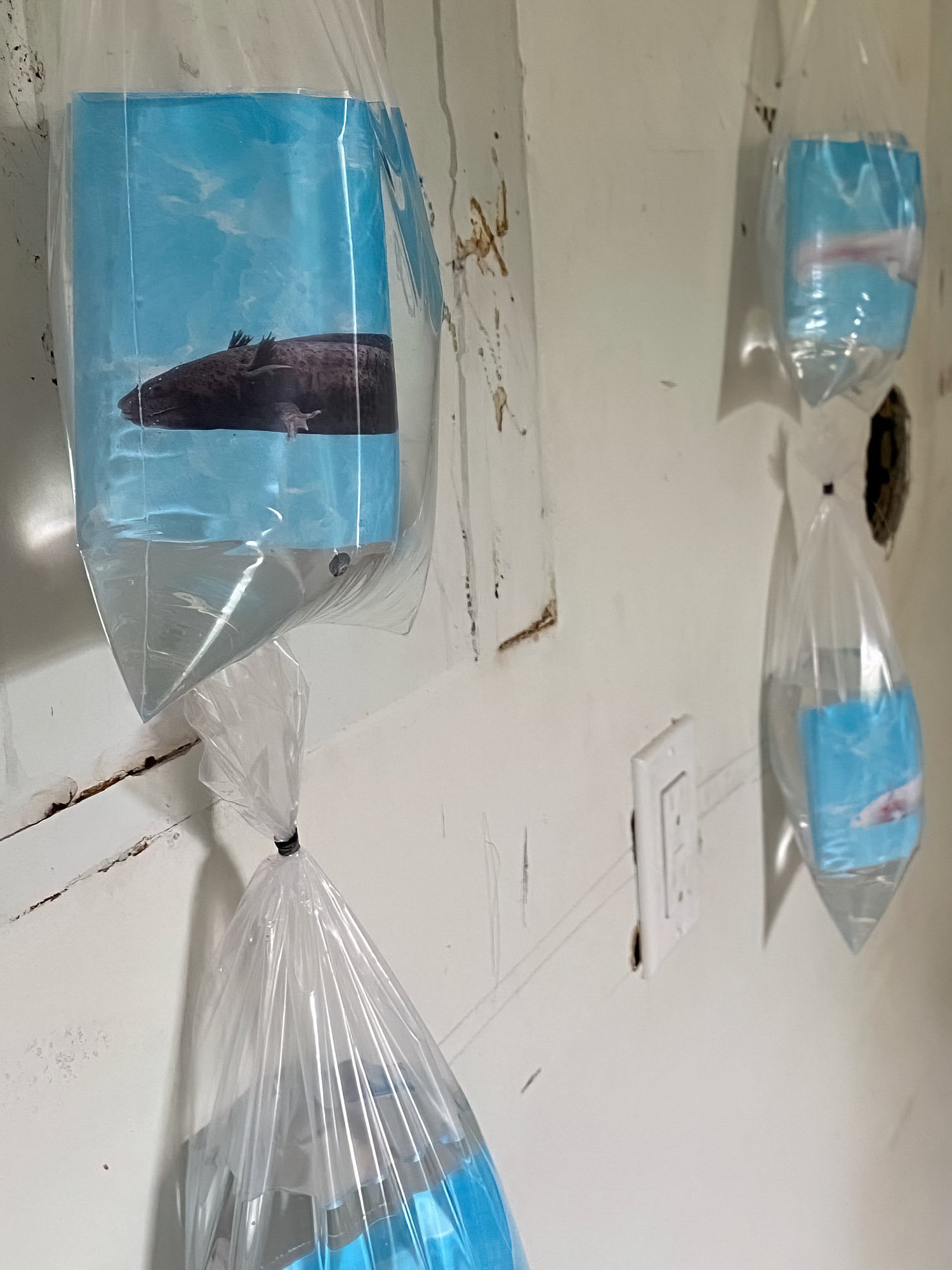

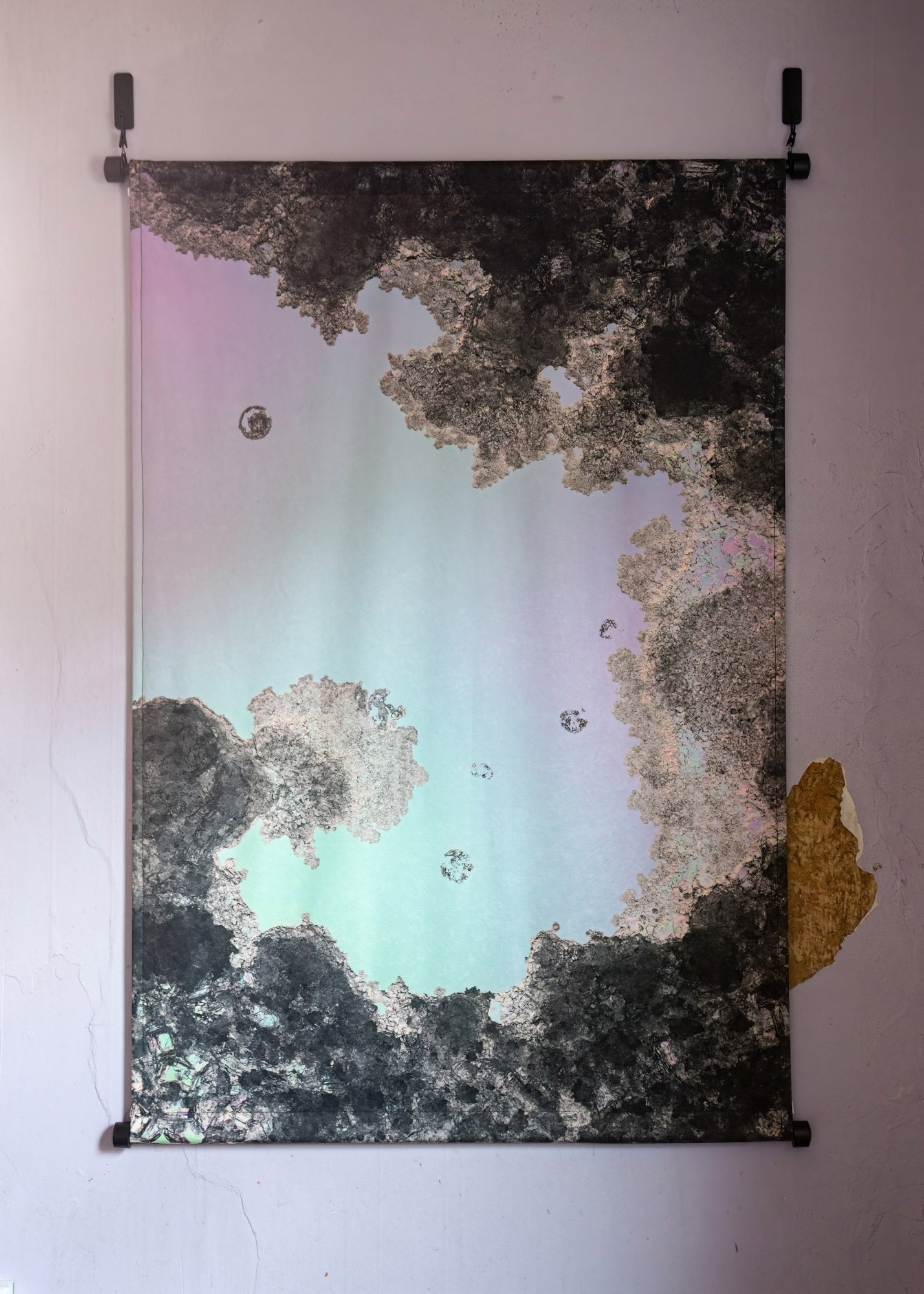

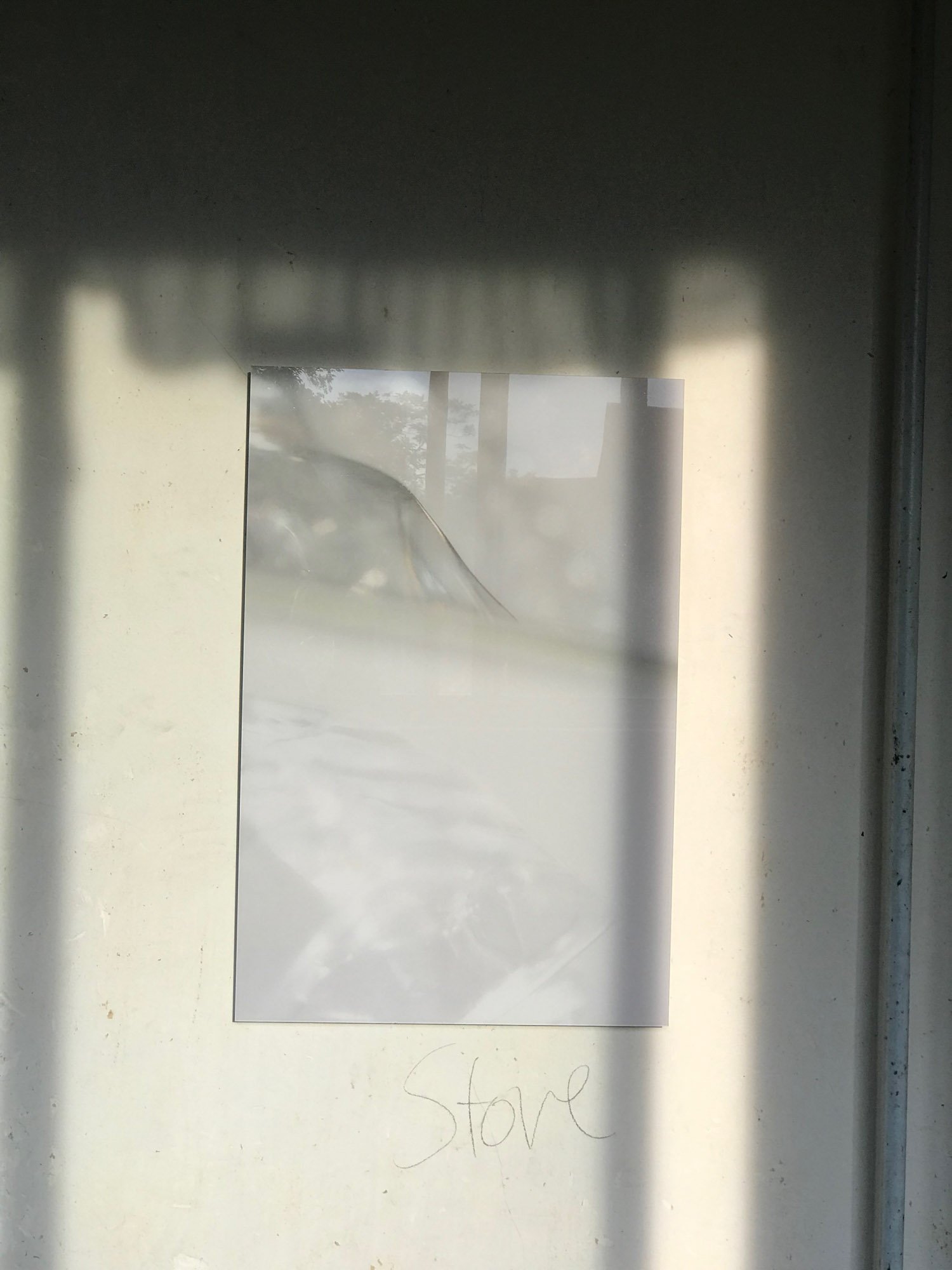

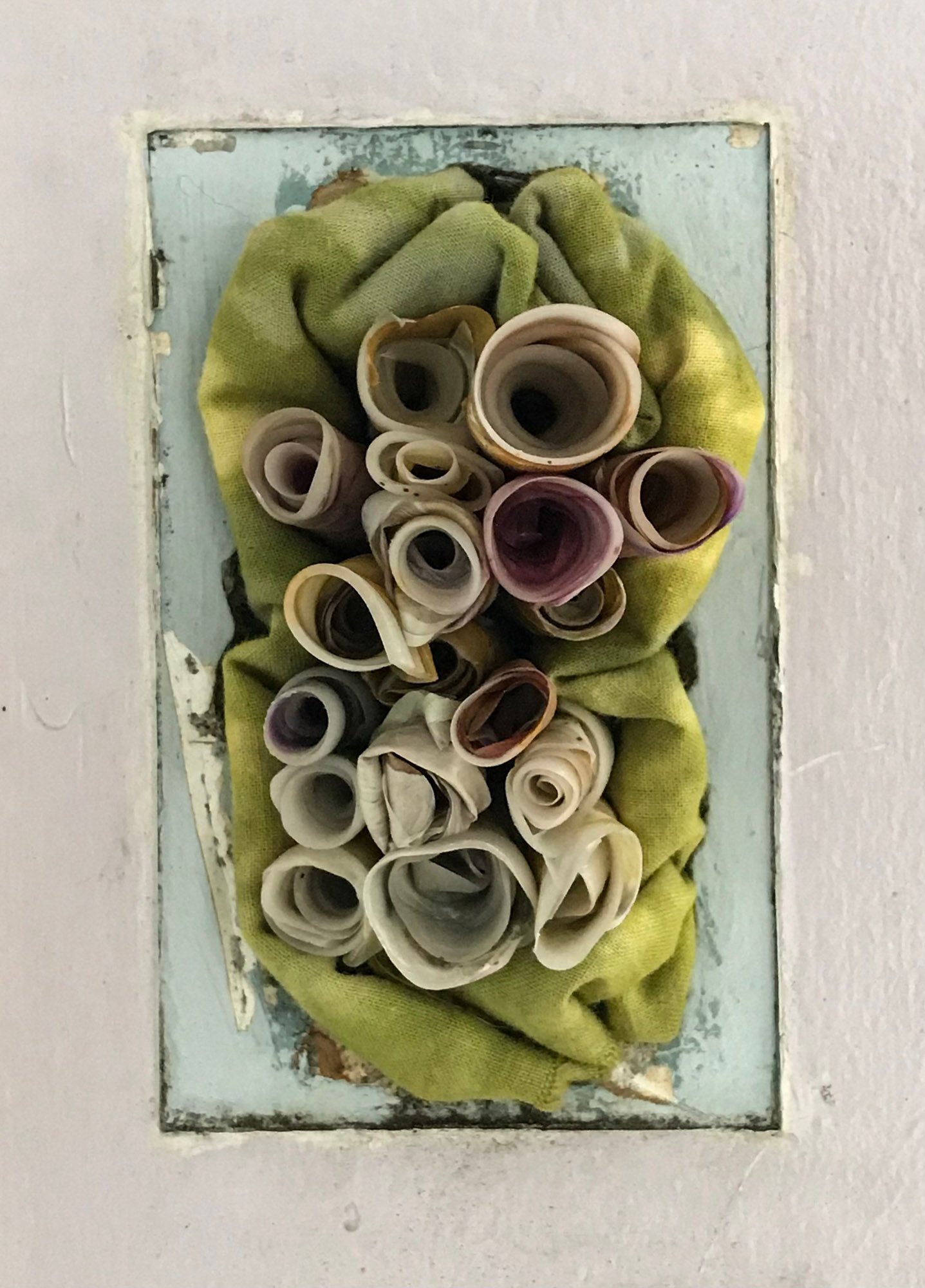

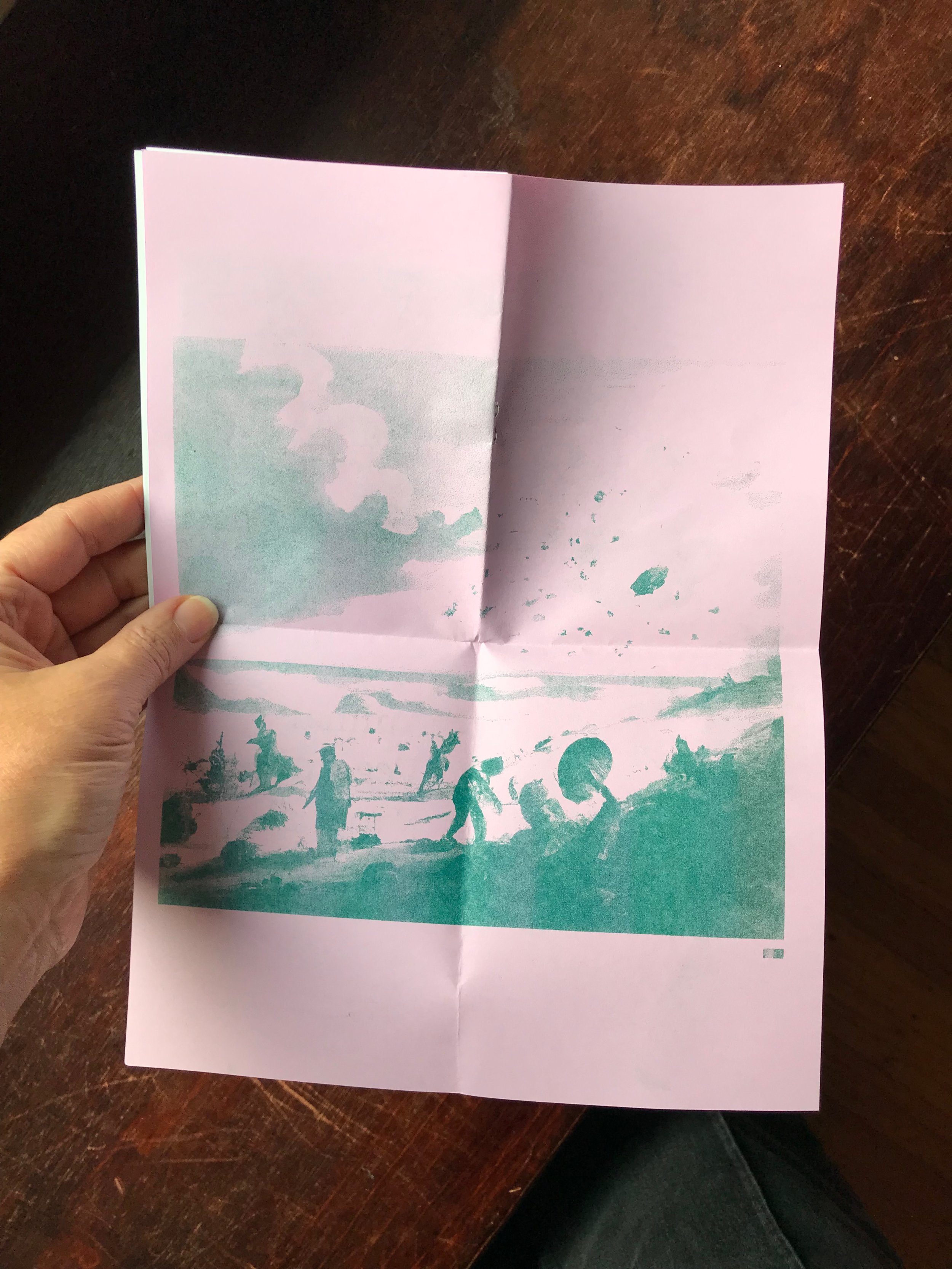

These are lenticular prints, which use very small-scale prisms to visually merge multiple images. This type of printing became popular in the second half of the 20th century as a format for things like political badges, travel souvenirs, holy cards, and the kind of small toys you might find in a cereal box. Today’s forms of lenticular printing can merge dozens of video frames, create realistic 3D imagery, or even make the effect tiny and flat enough to fit on a postage stamp. The version you see here is the old-fashioned Crackerjack-prize type, which uses two matched photographs with different color effects. The two images are printed in precisely matched, alternating rows, which correspond with the linear lenses. Each little rib on the surface of the print works like a lens to refract what’s behind it, which will shift depending on the angle from which it is seen. As your point of view on the image moves, the image that each little lens directs at your eye will shift from one image to the other. If you’re viewing the lenticular images in person with binocular vision, each eye’s perspective will be slightly different. This creates the shimmering effect of these prints.

Hanging details

These prints are mounted on translucent colored acrylic, which will create a subtle color glow on the wall behind the image when the light is right. (This is artisanal small-batch laser cutting, which I do myself here in the Burgh.) They’re designed to hang casually, slightly off-square. If you want yours to be perfectly level, use poster adhesive strips instead.

Polarized light for color

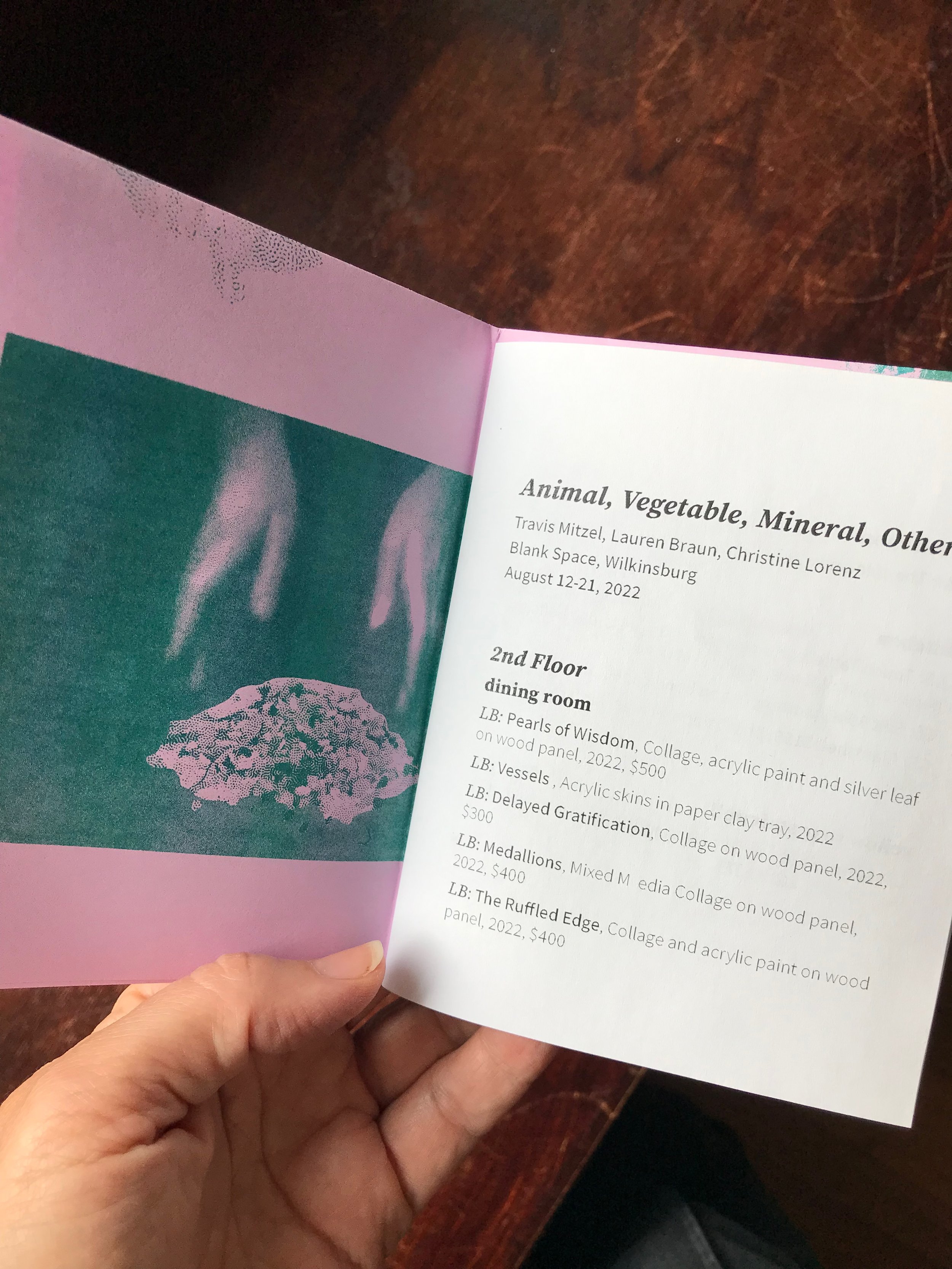

The crystals you see in these photographs are normal table salt, which has crystalized in a shallow, transparent acrylic dish. This dish is then elevated above a light source, which has been coupled with a polarizing filter. This forces the light to come through in synchronized waves. The light then passes through layers of transparent plastics, which act as retarders. These not technical tools; they’re ordinary single-use plastics, mostly from product packaging. These are chosen for their ability to diffuse the light waves very slightly—just enough to create color effects that further refract when the light waves hit the salt crystals. The camera is pointing straight down at the crystals (and the layers of light, polarizing filter, and plastic retarders beneath them). There’s an additional polarizing filter on the camera that enhances the color effects, and rotating this filter shifts the range of colors that are visible.